From Ancient Civilizations to Modern Practice – A Journey Through the World of Wizards, Sorcerers, and Magical Arts

Wizardry represents one of humanity’s oldest and most captivating pursuits, the quest to understand, harness, and manipulate the unseen forces that shape our world. For thousands of years, wizards have occupied a unique space in human consciousness, serving as intermediaries between the mundane and the magical, the known and the unknowable.

From the temple priests of ancient Mesopotamia to the cunning folk of medieval Europe, from the shamans of indigenous cultures to the modern practitioners of ceremonial magic, the figure of the wizard has remained a constant presence throughout human history. The practice of wizardry encompasses far more than the theatrical imagery of pointed hats and flowing robes popularized by contemporary fantasy. It represents a sophisticated system of knowledge, ritual, and practice that has evolved across millennia and cultures.

The practice of wizardry encompasses far more than the theatrical imagery of pointed hats and flowing robes popularized by contemporary fantasy. It represents a sophisticated system of knowledge, ritual, and practice that has evolved across millennia and cultures.

Wizardry involves the study of natural forces, celestial movements, herbalism, symbolism, and the human psyche itself. It is both an art and a science, combining intuition with meticulous observation, spiritual insight with practical application.

The Ancient Roots of Wizardry

Mesopotamian Beginnings: The First Recorded Magic

The cradle of civilization was also the birthplace of recorded wizardry. In ancient Mesopotamia, roughly 3000 BCE, priests and priestesses known as the āšipu practiced what may be history’s first formalized system of magic. These early wizards served in temples dedicated to gods like Marduk and Ishtar, performing elaborate rituals designed to divine the future, heal the sick, and ward off evil spirits.

The Mesopotamians developed extensive magical texts, including incantations written in cuneiform script on clay tablets. These spells addressed everything from medical ailments to agricultural concerns, from love magic to protection against demons. The famous Maqlû series, a collection of anti-witchcraft rituals, demonstrates the sophistication of their magical practice. These ancient wizards understood magic as a practical tool for navigating daily life and maintaining cosmic order.

Egyptian Magic: The Power of Heka

Ancient Egyptian civilization elevated wizardry to a divine principle. The Egyptians called magic heka, personified as a god and considered one of the fundamental forces used by the creator deity to bring the universe into existence. This meant that wizardry wasn’t merely a human practice but a cosmic power that predated creation itself.

Egyptian priests-wizards wielded tremendous authority, serving as intermediaries between gods and mortals. They mastered the art of hieroglyphic spells, creating the famous Pyramid Texts and Book of the Dead—compilations of magical formulae designed to ensure safe passage through the afterlife. These texts contained transformation spells, protective incantations, and rituals for communicating with deities.

The legendary Egyptian wizards became famous throughout the ancient world. Figures like Imhotep, the architect of the Step Pyramid who was later deified and associated with healing magic, exemplified the wizard as sage, builder, and mystical practitioner. Egyptian magical practice influenced neighboring cultures for centuries, spreading throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond.

Greek and Roman Mysticism

The classical world inherited and transformed ancient magical traditions. Greek culture produced legendary wizard-philosophers like Pythagoras, who combined mathematics, music, and mysticism into a comprehensive worldview. The Greeks developed the concept of goetia (sorcery) and theurgy (divine magic), distinguishing between lower forms of magic concerned with material manipulation and higher forms aimed at spiritual ascension.

Figures like Apollonius of Tyana became renowned throughout the Roman Empire as miracle-workers and wise men, blurring the lines between philosopher, wizard, and divine messenger. The Greek Magical Papyri, discovered in Egypt but written in Greek, preserved hundreds of spells, rituals, and magical procedures that combined Egyptian, Greek, and Near Eastern traditions into a sophisticated syncretic system.

Roman culture both feared and utilized wizardry. While laws existed against harmful magic (maleficium), protective magic and divination remained widely practiced. Roman augurs read omens in bird flights and animal entrails, while practitioners of the mysterious Eleusinian Mysteries promised initiates profound spiritual transformation through secret magical rites.

Medieval Wizardry: The Age of Grimoires and Secret Knowledge

The Islamic Golden Age and Magical Science

While medieval Europe struggled through its so-called Dark Ages, Islamic civilization experienced a golden age of learning that significantly advanced magical arts. Islamic scholars preserved and expanded upon ancient Greek and Roman magical texts, translating works of Hermetic philosophy and astrological magic. Cities like Baghdad, Cairo, and Córdoba became centers of mystical learning where wizardry, astronomy, mathematics, and medicine intertwined.

The tradition of Islamic magic emphasized the power of divine names and numerology. Practitioners developed complex talismanic magic based on mathematical squares and Arabic letters. The famous Shams al-Ma’arif (The Book of the Sun of Gnosis), attributed to Ahmad al-Buni, became one of the most influential grimoires in Islamic magic, containing instructions for creating powerful talismans and invoking spiritual entities.

European Medieval Magic: Between Church and Cunning Folk

Medieval European wizardry existed in a complex relationship with Christianity. On one hand, the Church condemned many magical practices as heretical or demonic. On the other hand, Christian monks preserved and copied ancient magical texts, and religious ritual itself incorporated elements of what could be considered magical practice—the transformation of bread and wine, the power of holy relics, exorcisms, and blessings.

The medieval period saw the flourishing of grimoire literature—books of magical instruction that claimed to teach readers how to conjure spirits, create talismans, and perform wonders. Works like the Key of Solomon (Clavicula Salomonis), the Lesser Key of Solomon (Lemegeton), and the Book of Abramelin became foundational texts of Western ceremonial magic. These grimoires typically combined Jewish Kabbalah, Christian prayer, astrological timing, and ritual procedure into comprehensive magical systems.

At the village level, cunning folk—local magical practitioners—provided essential services to communities. These wizards healed illnesses, found lost objects, crafted protective charms, identified thieves, and counteracted the harmful magic of witches. Unlike the learned magicians who worked from ancient texts, cunning folk relied on oral tradition, folk knowledge of herbs and natural magic, and claimed relationships with helpful spirits or fairies.

Famous Medieval Wizards

Medieval Europe produced numerous legendary wizards whose reputations endured for centuries. Albertus Magnus, a thirteenth-century Dominican friar, achieved fame as both a theologian and a natural philosopher with reputed magical abilities. Roger Bacon, the English Franciscan friar, became known as “Doctor Mirabilis” for his scientific experiments and allegedly magical inventions.

Perhaps most famous was the historical figure behind the Faust legend—several German alchemists and magicians of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries who claimed to have mastered demonic magic. These tales of wizards making pacts with demons for ultimate knowledge and power captured medieval imagination and influenced literature for centuries.

The Renaissance and Occult Revival

Hermetic Philosophy and High Magic

The Renaissance witnessed an extraordinary revival of interest in ancient magical texts. When the Byzantine Empire fell in 1453, Greek scholars fled westward bringing with them ancient manuscripts. The rediscovery of the Corpus Hermeticum—texts attributed to the mythical Egyptian sage Hermes Trismegistus—electrified European intellectual circles.

Renaissance wizards like Marsilio Ficino and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola integrated Hermetic philosophy, Neoplatonism, Kabbalah, and Christian theology into sophisticated systems of natural and ceremonial magic. These scholars believed that the universe was fundamentally unified and that a wise practitioner could learn to manipulate the hidden correspondences linking celestial bodies, earthly materials, and spiritual forces.

This period produced some of history’s most influential magical philosophers. Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa authored the encyclopedic Three Books of Occult Philosophy, systematizing magical knowledge from ancient through Renaissance sources. Paracelsus revolutionized medicine by combining alchemical theory with medical practice, treating illness through an understanding of spiritual and material forces.

The Age of Alchemy

Alchemy represented wizardry’s laboratory science—the attempt to understand and transform matter through both practical experimentation and spiritual development. While popularly known for the quest to transmute base metals into gold, alchemy encompassed much more. Alchemists sought the Philosopher’s Stone, a legendary substance that could perfect matter and grant immortality. They developed the theory of the four elements, experimented with distillation and chemical processes, and created an elaborate symbolic language to encode their discoveries.

The alchemical Great Work represented both a physical and spiritual journey. External operations in the laboratory mirrored internal transformations of the practitioner’s soul. Famous alchemists like Nicolas Flamel (whose legendary success in creating the Philosopher’s Stone made him immortal in stories, if not fact) and John Dee (court astrologer to Queen Elizabeth I and creator of Enochian magic) exemplified the Renaissance wizard-scientist who saw no contradiction between magical practice and natural philosophy.

Wizardry Across World Cultures

Asian Magical Traditions

Eastern cultures developed rich traditions of wizardry parallel to Western practices. Chinese Taoism produced its own class of wizard-priests who practiced internal alchemy, feng shui, astrology, and ritual magic. The fangshi (method masters) of ancient China claimed abilities to commune with spirits, achieve immortality through elixirs, and manipulate natural forces through understanding of yin and yang principles.

Japanese onmyōji (practitioners of onmyōdō) served as official diviners and magicians in the imperial court. These wizards specialized in astrology, creating calendars, divination, and performing rituals to ward off evil influences. The legendary Abe no Seimei became Japan’s most famous onmyōji, appearing in countless stories as a master of mystical arts who could control spirits and divine hidden truths.

Indian traditions produced sophisticated systems of tantric magic, combining yogic practices, mantra recitation, and ritual procedures. Practitioners sought both worldly powers (siddhis) and spiritual liberation through mastery of esoteric techniques. The manipulation of sacred sound, visualization practices, and complex ritual geometry created a unique form of wizardry focused on consciousness transformation.

African and Indigenous American Magic

African magical traditions emphasized the wizard’s role as a community protector and healer. The nganga of Central Africa, the sangoma of Southern Africa, and countless other traditional healers across the continent practiced complex systems of herbalism, spirit communication, and divination. These practices survived the Atlantic slave trade, evolving into syncretic traditions like Hoodoo, Vodou, and Santería that combined African, European, and indigenous American elements.

Native American cultures developed their own wizard traditions, with medicine men and women serving as healers, visionaries, and ceremonial leaders. These practitioners used drums, rattles, sacred plants, and elaborate rituals to enter altered states and commune with spirit powers. Vision quests, sweat lodge ceremonies, and medicine bundles represented sophisticated magical technologies adapted to specific geographical and cultural contexts.

Norse and Celtic Wizardry

Northern European cultures revered their own magical practitioners. Norse seiðr practitioners, often associated with the god Odin, performed rituals involving trance states, prophecy, and shape-shifting. The völva (seeress) traveled between communities performing divination and magical services.

Celtic druids functioned as priests, judges, teachers, and wizards within their societies. Though much of their knowledge was lost when Roman conquest disrupted Celtic culture, surviving accounts describe druids as masters of natural philosophy, poetry, law, and magic who trained for up to twenty years to master their art. Their magical practice emphasized connection with nature, the power of sacred groves, and the mystical properties of certain trees and plants.

The Enlightenment and Transformation of Magic

The Scientific Revolution’s Challenge

The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries’ scientific revolution fundamentally challenged traditional wizardry. Natural philosophers like Isaac Newton (who secretly practiced alchemy) began explaining natural phenomena through mathematics and mechanics rather than occult forces. The Age of Reason subjected magical claims to empirical testing, and many practices were dismissed as superstition.

However, wizardry didn’t disappear—it transformed. The Enlightenment’s emphasis on reason paradoxically helped preserve magical traditions by encouraging their systematization and documentation. Freemasonry emerged, incorporating ceremonial magic into its symbolic rituals. The Rosicrucian movement claimed possession of secret ancient wisdom, attracting intellectuals seeking alternatives to purely materialistic worldviews.

The Occult Revival of the 19th Century

The nineteenth century witnessed a remarkable resurgence of interest in wizardry and occult practices. Spiritualism swept through America and Europe, with mediums claiming to communicate with the dead. Madame Blavatsky founded Theosophy, blending Eastern philosophy with Western occultism. The French occultist Éliphas Lévi revived interest in ceremonial magic and Tarot, influencing generations of later practitioners.

This period saw the founding of magical orders dedicated to systematic study and practice of wizardry. The Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, established in 1887, became perhaps the most influential magical organization in Western history. Its members included poet W.B. Yeats and future ceremonial magic innovator Aleister Crowley. The Golden Dawn synthesized Kabbalah, astrology, alchemy, Tarot, and ritual magic into a comprehensive training system for aspiring wizards.

Wizardry in the Modern Age

Aleister Crowley and Thelema

The twentieth century’s most notorious wizard, Aleister Crowley, revolutionized modern magical practice. Crowley founded Thelema, a philosophical and magical system based on the principle “Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the Law.” His prolific writings, including Magick in Theory and Practice, attempted to strip away superstition and approach wizardry as a science of consciousness and will.

Crowley’s influence extended far beyond his immediate circle. His emphasis on individual spiritual development, his synthesis of Eastern and Western practices, and his willingness to experiment with controversial techniques shaped virtually all subsequent Western ceremonial magic. Whether admired or reviled, Crowley forced a confrontation between Victorian occultism and modernist sensibilities.

Wicca and Neo-Paganism

The mid-twentieth century saw the emergence of Wicca, founded by Gerald Gardner and claiming to preserve ancient pre-Christian witchcraft traditions. While historians debate Wicca’s actual antiquity, the religion successfully combined ceremonial magic, folk practices, and goddess worship into an appealing modern system. Wicca emphasized nature veneration, seasonal celebrations, and magical workings focused on healing and positive change.

Wicca sparked broader neo-pagan movements that reconstructed or reimagined ancient polytheistic religions. Practitioners of Asatru revived Norse paganism, while others explored Hellenic, Celtic, or Egyptian traditions. These movements demonstrated that wizardry remained vibrant and meaningful to contemporary practitioners seeking alternatives to mainstream religions.

Chaos Magic and Postmodern Wizardry

Late twentieth-century occultism produced chaos magic, a deliberately iconoclastic approach to wizardry. Chaos magicians argued that belief itself was the primary tool of magic—that wizards could achieve results by temporarily adopting any belief system, mythological framework, or symbolic set. This radically pragmatic approach stripped away magical tradition’s elaborate cosmologies, focusing solely on what worked.

Authors like Peter J. Carroll and Phil Hine advocated for experimental approaches to magic. Chaos magicians created sigils (symbolic representations of intentions), practiced gnosis (altered states of consciousness), and incorporated pop culture symbols alongside traditional magical imagery. This democratization of wizardry suggested that anyone could become a competent practitioner through experimentation rather than lengthy traditional training.

Contemporary Wizardry: Digital Age Magic

The Internet’s Transformation of Magical Knowledge

The digital revolution democratized access to magical knowledge in unprecedented ways. Grimoires once locked in rare book collections became available as PDFs. Online forums connected practitioners globally, enabling rapid exchange of techniques and experiences. Social media platforms hosted thriving magical communities where wizards shared their practices openly.

This accessibility transformed wizardry from an exclusive pursuit requiring access to rare teachers or texts into something anyone with internet connection could explore. YouTube tutorials explained complex rituals. Apps provided daily Tarot readings. Virtual magical lodges conducted initiations via video conference. The digital age fundamentally changed how people learn and practice wizardry.

Psychological and Therapeutic Approaches

Contemporary practitioners increasingly interpret wizardry through psychological lenses. Rather than viewing magic as manipulation of external supernatural forces, many modern wizards understand magical practice as sophisticated techniques for influencing consciousness, emotion, and unconscious processes. Ritual becomes theater for the psyche. Divination systems like Tarot become tools for introspection and decision-making.

This psychological approach doesn’t necessarily deny magic’s effectiveness—instead, it reframes the mechanism. Carl Jung’s concept of archetypes and the collective unconscious provided explanatory frameworks that made sense to modern practitioners. Psychologists like Israel Regardie (himself a magician) explicitly connected ceremonial magic with depth psychology.

Scientific Interest in Consciousness

Recent decades have seen renewed scientific interest in phenomena long associated with wizardry. Research into meditation, psychedelics, near-death experiences, and altered states of consciousness has revealed that human consciousness is far stranger and more malleable than previously assumed. Studies of placebo effects, meditation’s neurological impacts, and the relationship between belief and healing outcomes suggest that consciousness-focused practices may indeed produce measurable effects.

Some modern practitioners frame wizardry as an anticipatory technology—a set of empirical practices developed through centuries of experimentation that mainstream science is only beginning to understand. From this perspective, wizards were always proto-psychologists and consciousness explorers, developing practical techniques for self-transformation that science now validates through different terminology.

Wizardry in Popular Culture

Literary Tradition

Fiction has powerfully shaped modern understanding of wizardry. Tolkien’s Gandalf, Le Guin’s Ged, Rowling’s Dumbledore—these fictional wizards have become more culturally influential than most historical practitioners. The fantasy genre established archetypal wizard figures: the wise mentor, the power-hungry dark sorcerer, the young apprentice discovering their abilities.

These literary wizards often embody philosophical themes. Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea series explored the relationship between names, power, and identity. Terry Pratchett’s Discworld wizards satirized academic institutions while exploring genuine magical philosophy. Patrick Rothfuss’s The Name of the Wind presented magic as both art and science requiring rigorous study.

Film, Television, and Gaming

Visual media brought wizardry to life for global audiences. The Harry Potter film series made magical practice seem tangible and exciting to millions. Television shows like The Magicians explored darker, more adult perspectives on magical training. Anime series like Fate/Stay Night combined magical lore with contemporary settings.

Video games created interactive experiences of wizardry, allowing players to virtually practice spellcasting, potion-making, and magical combat. Role-playing games from Dungeons & Dragons to The Elder Scrolls series encouraged players to imagine themselves as wizards, making choices about how to develop and use their magical abilities. These games often drew from genuine magical traditions, introducing millions to concepts like elemental magic, summoning, and ritual practice.

Cultural Impact

Popular culture’s wizards have influenced real magical practice as much as historical traditions have influenced fiction. Practitioners adopt spellcasting methods from fantasy novels. Magical tools inspired by films become actual ritual implements. The aesthetic of fantasy wizardry—robes, staffs, spellbooks—has been embraced by contemporary practitioners who might once have preferred suits and ties.

This cross-pollination demonstrates wizardry’s living nature. Rather than being a fossilized remnant of pre-scientific thinking, magical practice continues evolving, incorporating new symbols and narratives that resonate with contemporary consciousness. Today’s wizard might invoke Gandalf with the same reverence medieval practitioners showed Solomon.

Schools of Contemporary Magical Practice

Ceremonial Magic

Modern ceremonial magic maintains elaborate ritual traditions descended from medieval grimoires and nineteenth-century magical orders. Practitioners work with complex correspondences linking colors, planets, angels, demons, Hebrew letters, and Tarot cards into comprehensive systems. They perform lengthy rituals involving purification, invocation, and banishing procedures designed to create sacred space and contact spiritual entities.

Organizations like the Ordo Templi Orientis, the Builders of the Adytum, and various Golden Dawn successor orders continue training wizards in these traditional methods. Students progress through degree systems, learning increasingly complex magical operations. Despite its medieval trappings, ceremonial magic remains actively practiced by thousands worldwide.

Witchcraft and Wicca

Contemporary witchcraft emphasizes personal practice, connection with nature, and working with cycles and seasons. Wiccans celebrate eight seasonal festivals marking solstices, equinoxes, and cross-quarter days. They practice magic through spellcasting, working with herbs and crystals, and honoring deities from various pantheons.

Many modern witches identify as eclectic, combining practices from multiple traditions rather than adhering to single lineage. Online communities have fostered this eclecticism, with practitioners freely sharing techniques and innovations. This accessibility has made witchcraft one of the fastest-growing spiritual movements in the Western world.

Energy Work and New Age Practices

New Age movements emphasize working with subtle energies and consciousness. Practitioners might work with chakras (from Hindu tradition), practice Reiki healing, or use crystal grids to direct energy. These approaches tend to focus on personal development, healing, and manifestation rather than traditional occult goals.

While sometimes dismissed by traditional occultists as simplistic, energy work represents a genuine evolution of magical practice adapted to contemporary needs and sensibilities. Its emphasis on accessibility and positive application has attracted millions who might not identify with more formal wizardry traditions.

Folk Magic Revival

Recent years have seen renewed interest in folk magic traditions from specific cultural contexts. Practitioners research and revive practices like Pennsylvania Dutch pow-wow, Italian stregheria, Appalachian folk magic, and various forms of rootwork. This represents a turn toward culturally-specific practices rather than synthesized universal systems.

This revival emphasizes magic as embedded in community, tradition, and place rather than abstract philosophy. Practitioners value simplicity, accessibility, and connection to ancestral practices. Grimoires like the Long Lost Friend and books on traditional cunning craft have found new audiences seeking authentic, practical magical approaches.

The Practice of Wizardry: Core Elements

Study and Knowledge

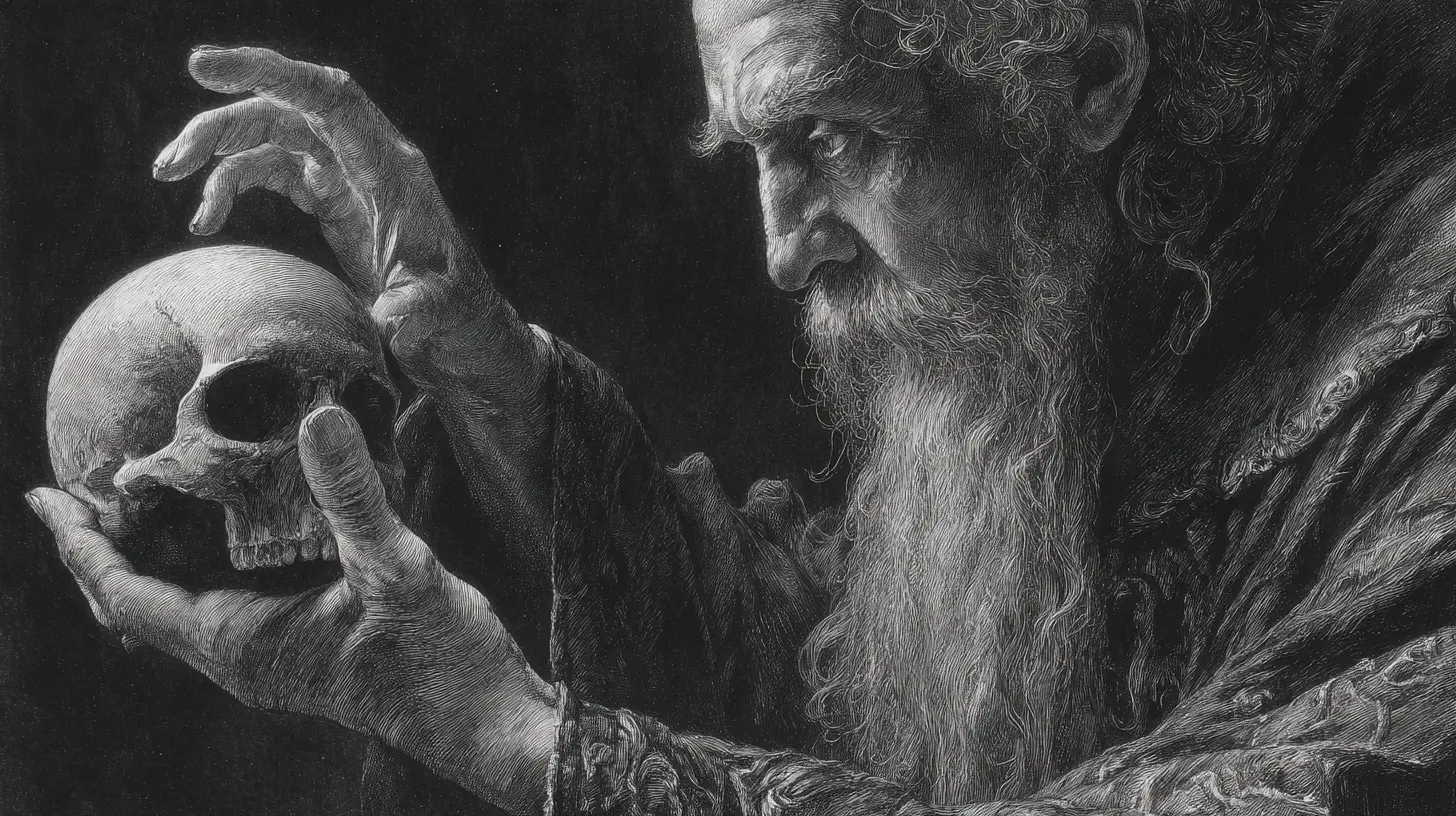

All wizardry traditions emphasize knowledge acquisition. The wizard must study—whether ancient grimoires, planetary correspondences, herbal properties, or psychological dynamics. This intellectual component distinguishes wizardry from purely intuitive spiritual practices. The image of the wizard surrounded by books reflects genuine necessity. Effective magical practice requires understanding symbols, timing, materials, and procedures.

Modern wizards have unprecedented access to magical texts from all traditions and eras. The challenge has shifted from finding information to developing discernment about what to study. Aspiring practitioners must balance breadth (exposure to diverse systems) with depth (mastery of specific practices). Many traditions recommend starting with a single coherent system before exploring eclectically.

Ritual and Ceremony

Ritual provides structure for magical work. Whether elaborate ceremonial invocations or simple candle spells, rituals create psychological and energetic frameworks for focused intention. They typically involve preparation (purification, assembling materials), execution (performing specific actions in prescribed order), and conclusion (grounding, banishing, giving thanks).

Effective ritual engages multiple senses and levels of consciousness. Incense provides scent, candles provide light, chanting engages voice, movements engage body. This multi-sensory engagement helps shift consciousness into states conducive to magical work. The formality of ritual also communicates seriousness of intent to unconscious levels of mind.

Symbolism and Correspondences

Wizardry operates through symbolic language. Practitioners work with correspondences—relationships linking material objects, colors, planets, deities, emotions, and abstract concepts. A spell for Mars energy might incorporate red candles, iron, Tuesday timing, aggressive music, and martial deity invocation. These correspondences create resonance, aligning multiple elements toward single purpose.

Understanding symbolism allows wizards to customize practices meaningfully. Rather than following recipes blindly, competent practitioners understand the logic behind associations and can adapt or substitute intelligently. This requires studying how different systems organize correspondences—elemental, planetary, Kabbalistic, and others.

Altered States of Consciousness

Virtually all magical traditions employ techniques for entering altered states. These might include meditation, rhythmic drumming, chanting, breathing exercises, visualization, fasting, sensory deprivation, or psychoactive plants. Altered states facilitate magical work by accessing intuitive awareness, reducing critical thinking that might inhibit effects, and connecting with deeper levels of consciousness.

The wizard must develop ability to enter and exit these states reliably and safely. This requires practice and discipline. Many traditions emphasize daily meditation or similar practices to develop this fundamental skill. The goal isn’t losing control but rather accessing expanded awareness while maintaining intentional direction.

Will and Intention

Ultimately, all magic requires focused will. The wizard must clearly formulate intention, concentrate attention, and direct energy toward desired outcome. This sounds simple but proves challenging. Human minds naturally wander. Doubts arise. Conflicting desires interfere. Much magical training involves developing sustained concentration and coherent will. Different traditions frame will differently—as connection with higher self, alignment with universal forces, or psychological programming of unconscious. Regardless of theory, practice requires the same cultivation of focused intention. The wizard must know precisely what they want and commit fully to achieving it.

Ethics and Responsibility in Wizardry

The Question of Harm

Magical ethics have been debated throughout history. Some traditions embrace the Wiccan Rede—”An it harm none, do what ye will”—as fundamental principle. Others acknowledge that all action creates ripples and that sometimes forceful magic may be necessary. Historical grimoires often contained curses and binding spells alongside healing and protection magic.

Contemporary practitioners must navigate these questions individually. Most agree that magic shouldn’t be used manipulatively—attempting to override others’ free will or cause unnecessary harm. However, defensive magic, justice work, and forceful boundary-setting remain controversial. Each practitioner must develop their own ethical framework based on careful consideration of consequences and personal values.

The Threefold Law and Karmic Consideration

Many modern magical traditions teach that energy returns to its sender, sometimes multiplied. This “threefold law” or karmic principle encourages careful consideration before magical work. If cursing someone will result in worse harm returning to you, malicious magic becomes practically inadvisable regardless of theoretical ethics.

Critics note that this law appears nowhere in historical magical texts and may represent modern innovation. Regardless of metaphysical validity, the principle encourages beneficial practice and personal accountability. The wizard who considers potential consequences before acting develops wisdom alongside power.

Psychological and Social Responsibility

Modern practitioners increasingly emphasize psychological and social dimensions of magical ethics. Claiming magical power can inflate ego or enable avoidance of practical action. Spiritual bypassing—using magical or spiritual beliefs to avoid dealing with psychological issues or social responsibilities—represents a genuine danger.

Responsible wizardry complements rather than replaces practical action. The practitioner who performs a money spell while refusing to seek employment demonstrates magical thinking rather than genuine practice. Mature wizards integrate magical and mundane approaches, using each where appropriate.

Scientific Perspectives on Magical Practice

The Psychology of Magic

Psychological research offers frameworks for understanding magical practice without necessarily invalidating it. Ritual can be understood as structured consciousness modification. Symbolism accesses unconscious processing. Meditation and altered states affect neurology measurably. Placebo effects demonstrate mind’s influence over body.

From this perspective, wizardry represents sophisticated psychological technology developed through millennia of empirical experimentation. Whether or not supernatural forces exist, magical practices demonstrably affect consciousness, emotion, and behavior. This makes them worthy of serious study regardless of one’s metaphysical commitments.

Anthropological Understanding

Anthropology recognizes magic as universal human phenomenon serving important social and psychological functions. Magical practice helps communities process uncertainty, maintain social cohesion, and mark important transitions. Wizards serve as specialists in managing the sacred, negotiating between ordinary and extraordinary realms.

Rather than dismissing magic as primitive superstition, contemporary anthropology recognizes it as sophisticated cultural technology. The symbolic systems and ritual procedures developed by magical traditions represent accumulated wisdom about human consciousness, social dynamics, and meaning-making.

Quantum Mysticism and Scientific Speculation

Some attempt to explain magical phenomena through quantum physics, consciousness studies, or holographic universe theories. While mainstream scientists generally dismiss such connections as misunderstanding or misappropriation of scientific concepts, the conversation reflects enduring human desire to integrate mystical and scientific worldviews.

Serious practitioners generally avoid simplistic quantum justifications while remaining open to possibility that consciousness may operate through principles not yet fully understood by science. The relationship between observer and observed in quantum mechanics, the hard problem of consciousness, and anomalous findings in parapsychology research suggest that reality may be stranger than materialist reductionism assumes.

Beginning the Wizard’s Path

Self-Study Resources

Aspiring wizards today enjoy unprecedented access to learning resources. Classic texts like Agrippa’s Three Books of Occult Philosophy, the Key of Solomon, and Crowley’s works are freely available. Modern introductions like Donald Michael Kraig’s Modern Magick, Damien Echols’ High Magick, and countless Wiccan guidebooks provide accessible entry points.

Online communities offer support, instruction, and feedback. YouTube channels demonstrate ritual procedures. Podcasts interview experienced practitioners. Forums connect seekers with teachers. The challenge lies in discerning quality resources from misleading information. Newcomers should seek recommendations from established practitioners and compare multiple sources.

Finding Teachers and Communities

While self-study offers flexibility, learning from experienced practitioners accelerates development and prevents common mistakes. Local metaphysical shops often host classes and know about magical groups in the area. Online organizations like BOTA or OTO offer correspondence courses. Some practitioners offer apprenticeships or mentorship.

Community provides essential support and accountability. Practicing with others creates energetic synergy and expands perspective. However, seekers should carefully evaluate potential teachers and groups. Legitimate magical organizations emphasize personal development, ethical practice, and reasonable progression. Warning signs include demands for large sums of money, pressure to cut ties with family, or claims of unique secret knowledge available nowhere else.

Developing a Personal Practice

Ultimately, effective wizardry requires consistent personal practice. This typically begins with daily meditation to develop concentration and awareness. Many traditions recommend keeping a magical journal to record experiences, track progress, and reflect on learning. Regular ritual practice—even simple candle spells or devotional exercises—develops skill and confidence.

The aspiring wizard should study systematically while also experimenting freely. Balance learning traditional methods with developing personal approaches. Pay attention to what resonates and what feels forced. Effective magical practice must align with practitioner’s genuine beliefs and inclinations. The goal isn’t performing perfect reproduction of historical techniques but developing authentic personal power.

The Future of Wizardry

Technological Integration

As technology becomes increasingly integrated with human consciousness, new forms of wizardry emerge. Virtual reality could create immersive ritual environments. Biofeedback devices might help practitioners track and optimize altered states. AI could serve as intelligent grimoires, customizing practices to individual needs. Brain-computer interfaces might eventually enable directly accessing and programming unconscious processes that magical ritual traditionally addressed indirectly.

These possibilities raise fascinating questions about technology as extension of magic rather than opposition to it. If magic represents consciousness technology, then tools extending consciousness naturally become magical tools. The wizard’s staff might become smartphone, the grimoire might become app, but the underlying principles of will, symbol, and consciousness remain relevant.

Global Synthesis

Increased global communication enables unprecedented cross-cultural exchange of magical knowledge. Practitioners can now study Tibetan Buddhism, Norse runes, Yoruba orisha worship, and Hermetic Kabbalah simultaneously. This creates both opportunity and challenge—the opportunity to develop truly comprehensive magical systems synthesizing global wisdom, but also the risk of superficial cultural appropriation.

The future likely holds both continued synthesis and renewed emphasis on cultural specificity. Some practitioners will develop eclectic global approaches while others dive deeply into particular traditional lineages. Both approaches have value. The essential question is whether practice is undertaken with respect, depth, and genuine commitment versus shallow consumerist spirituality.

Mainstream Acceptance

Magical practice has become increasingly normalized in contemporary culture. Tarot reading, crystal use, and meditation have moved from fringe to mainstream. Younger generations show greater openness to alternative spiritualities. This normalization makes magical practice more accessible but also risks commercialization and trivialization.

The challenge for serious practitioners will be maintaining depth and authenticity while engaging with growing popular interest. Wizardry has always balanced exoteric accessibility with esoteric depth. Future developments will likely continue this pattern—popular engagement with magical aesthetics and simpler practices alongside continuing traditions of serious study and transformative practice.

The Enduring Power of Wizardry

From Mesopotamian temple priests to modern chaos magicians, from Egyptian hierophants to teenage Wiccans casting spells in bedrooms, wizardry has demonstrated remarkable persistence across cultures and centuries. This endurance suggests that magical practice addresses fundamental human needs—the need for meaning, for agency in uncertain circumstances, for connection with forces larger than ourselves, for transformation of consciousness and life circumstances.

Whether understood as supernatural technology, psychological sophistication, or symbolic meaning-making, wizardry offers practitioners tools for navigating existence with greater intentionality and awareness. The wizard’s core skills—focused attention, symbolic thinking, ritual practice, altered states—remain valuable regardless of metaphysical commitments.

In an age of increasing technological power coupled with existential uncertainty, wizardry’s emphasis on personal development, ethical consideration, and consciousness exploration may prove more relevant than ever. The wizard represents a perennial human archetype—the seeker who studies hidden knowledge, develops inner power, and works to manifest will in reality. This archetype speaks to something deep in human nature that transcends specific cultural or historical circumstances.

As we move further into the twenty-first century, wizardry continues evolving while maintaining connection with ancient roots. New practitioners discover old grimoires. Ancient symbols find new applications. The fundamental practice of focusing consciousness to affect change remains as relevant in our digital age as it was in ancient Egypt. The path of the wizard—the way of knowledge, will, and transformation—continues calling those who hear its invitation to step beyond ordinary understanding and explore consciousness’s extraordinary capacities.

Whether you come to wizardry as spiritual practice, psychological technology, cultural tradition, or philosophical exploration, the door stands open. The grimoires await reading. The rituals await performance. The symbols await interpretation. The power awaits development. The ancient art of wizardry, having survived millennia of cultural transformation, remains accessible to any who choose to walk the path with sincerity, study, and commitment.

The wizard’s journey is ultimately a journey inward—to discover and develop the extraordinary potentials lying dormant within ordinary consciousness. In that sense, every person contains a wizard waiting to awaken. The only question is whether you will answer the call.